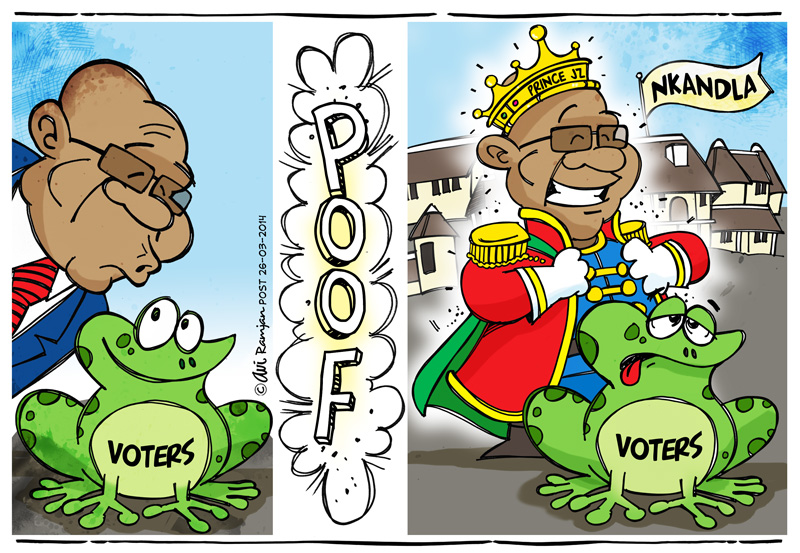

The ANC has reneged on a promise to invite SA into Nkandla by way of the media - but as a flip-flop it hardly registers compared to previous examples.

ANC secretary general Gwede Mantashe on Monday said the ANC would not, in fact, be arranging a media visit to Nkandla to show the country the truth about President Jacob Zuma's homestead.

The decision to invite South Africa into Nkandla, Mantashe said, had been reversed "because it became quite clear when we wanted to do that there were processes that were outstanding", including investigations by the Special Investigating Unit, possibly the Hawks, and a report by Zuma to Parliament. "Our view in hindsight, we took a view ... [to] not interfere with that space," he said.

Mantashe first said the ANC would arrange a visit to Nkandla in the interests of transparency before the end of last week.

"As we had committed when the report of the [internal government Nkandla investigation] was released, we will be inviting members of the media on a visit to the Prestige Project in Nkandla in the next week so that we can talk to the real issues beyond the report," Mantashe said on March 20.

But after the ANC's national executive committee met this past weekend, the ANC said various actions it could take, or demands it could make of Zuma, would amount to disrespect for constitutional institutions.

The reversal is the latest in a long line of flip-flops from the ANC, Zuma and various Cabinet ministers when it comes to Nkandla – and cancelling a media visit ranks well down the list. Some of the most notable include:

The president's bond documents are (not) available for inspection In November

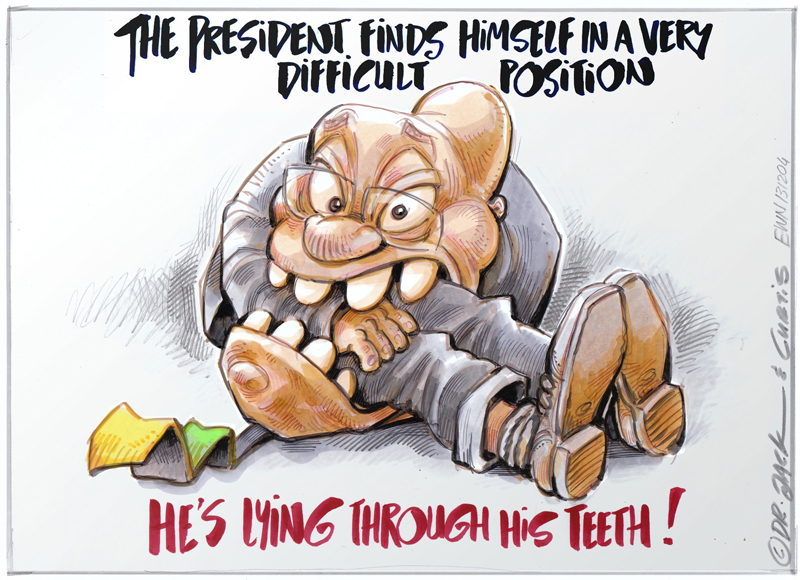

Zuma told Parliament that a bank funded his family's work on Nkandla. In an emotional session he defended himself fiercely against Nkandla allegations. "I am still paying a bond on the first phase of my home," said Zuma.

The presidency followed that up with a written media statement acknowledging requests for proof that the bond exists. "The evidence will be readily made available to an authorised agency or institution empowered by the law of the land," said presidential spokesperson Mac Maharaj.

After she, like many media organisations, could find no solid proof of the existence of such a bond, public protector Thuli Madonsela pointed Zuma to the statement, making it clear that her office surely qualifies.

"You will respectfully agree with me that this includes the public protector," Madonsela says she told Zuma, after multiple requests for the documents.

Zuma responded that the bond predated his taking office as president, so he could not see how the documents could be of interest in Madonsela's investigation.

"Accordingly, I hold the view that the disclosure you seek would be unnecessary," Zuma wrote to Madonsela.

The top-secret report that wasn't

In January 2013, Public Works Minister Thulas Nxesi released the results of the interministerial task team investigation into Nkandla, colloquially known as the government Nkandla report. The top finding: Zuma was neither culpable nor involved in the Nkandla scandal, and had not received personal benefit.

The actual report, however, was classified top-secret; so replete with security-sensitive information that it could not even be released in a redacted form.

The secrecy was strictly maintained. Parliament dealt with the report in a closed committee that handles matters of national security. Madonsela, during her investigation, was only given sight of the document and not allowed to make a copy.

But in December 2013 the ANC, by way of Mantashe, asked that the full report be released. Government announced just days later that it would release the report, and that was duly done. No adequate explanation was ever provided for the classification of the report, or for the change of heart.

Key point. No, ministerial handbook. No, actually, neither

The legal basis for the government spending, as it turned out nearly R250-million on Nkandla, has changed often enough to strain the definition of "flip-flop".

Initially the government said the work was done in terms of the apartheid-era National Key Points Act (NKPA), which also demanded secrecy regarding the improvements. That was reversed, if only in part, after it was pointed out that the NKPA would require Zuma to foot most of the bill, or for the money spent by the state to be drawn from a special account.

At other points Nxesi, as the de facto spokesperson on Nkandla, said the upgrades had been in terms of the Ministerial Handbook, a supposedly secret document that outlines the perks available to members of Cabinet. But the document had been published previously by the Mail & Guardian, and made no mention of presidential security. It did clearly say that state spending on the security of ministers at their private residences was capped at R100 000.

With little achieved other than making the point that the Nkandla bill was over 2000 times more than what was considered adequate for the tier of national leaders, that argument was also abandoned.

- M&G