The Western Cape, and the City of Cape Town in particular, faces an acute housing backlog of 400,000 - a number at the root cause of violent service delivery protests that sporadically disrupt parts of the City.

And with an influx of 2,000 new migrants every month, the number of houses being built by all spheres of government seems unlikely to significantly dent the backlog and alleviate the demand for housing.

The Western Cape’s backlog makes up a sizeable chunk of the national backlog of 2.15 million and is second only to Gauteng’s. Since April elections there have already been four service delivery protests, with frustration over a lack of housing the main reason given for the protests.

In the 16,000-strong Joe Slovo informal settlement, one of 223 informal settlements in the City that are home to 540,000 people, frustration with a lack of housing delivery runs high.

Gloria Qaga, 35, a mother of six children, said conditions in the informal settlement made her children sick and she could not raise them properly from her two-bedroom shack.

“The government does not care about us or care about what we want on our land. They are after money and if you don’t have it then tough luck,” she said.

Qaga said she had first registered for an RDP house in 1994, but had not heard anything. She then registered again in 2004, but had still not heard anything.

The settlement, in Langa, Cape Town’s oldest township, was identified as the site for the national government’s N2 Gateway Housing Project, which seeks to deliver 22,000 houses. But most residents have refused to move to a temporary relocation area in Delft, 40 kilometres away, to make way for the development.

Remaining residents have taken the fight against their eviction to the Constitutional Court, where a decision is pending.

They argue for the right to remain in the area, which is close to the city, employment prospects and services.

Although the N2 Gateway project is a national government initiative, the province and the municipality are also important players when it comes to housing delivery.

Alida Kotzee, the director of strategy support and coordination in the City’s housing directorate, said there were 306,801 applicants on the City’s housing database, but an additional 100,000 “guestimate” of people had not been registered and needed to be added.

Some of the people on this list might be housed in rental stock so not all where in need of shelter, but “all express the need to benefit from a housing subsidy and own a property through the subsidy process”.

Kotzee said the City experienced an influx of 2,000 people a month or 24,000 a year.

But according to Herman Steyn, the City’s manager of new housing, only 6,439 housing opportunities were provided in the 2007/08 year.

Even added to the provincial and national housing figures, it therefore appears unlikely that the backlog will be dented.

Western Cape housing department spokesperson Zalisile Mbali said over the last five years 76,924 houses had been provided.

Projected figures for the next three years were for an average of 16,000 houses per year. Assuming funding increased, 16,000 units would be delivered per annum for 2012/13 and 2013/14.

Mbali said given the backlog the department was placing emphasis on in situ upgrading of informal settlements. It was also moving to give full housing accreditation to the City of Cape Town and fostering public private partnerships.

- West Cape News

“We are tired of waiting”

Mavis Khuthala, 34, lives in a two-roomed shack in Joe Slovo informal settlement in Langa, Cape Town.

Made from wood and cardboard, the floor of the shack is sand, there are no windows and the household has to use a bucket toilet a block away. She shares the shack with eight children and one other adult.

Khuthala has been on the housing waiting list for 12 years, but although she has seen housing developments going up all around her she has yet to get a house.

She is one of 400,000 people in Cape Town on the housing waiting list.

“We are tired of waiting and nothing is being said to us about when we will get houses,” she said.

Khuthala said she had first registered with the City of Cape Town in 1997, but her name had never appeared on any lists of allocated houses.

She said she had registered again in 2004.

Later, when the N2 Gateway Housing Project, a national government project to deliver mass housing, was announced in 2005, she said she had hoped to be allocated a house, but had heard that only employed people who earned a monthly basic income would be allocated houses.

Khuthala is unemployed and her household survives on R720 pooled together from child support grants.

On numerous occasions in 2007 and last year, she said she had checked with the City of Cape Town to see if a house was available, but been told to “wait like everyone else”.

Khuthala takes care of her own five children and three belonging to her sister.

She spends most of her days in her shack taking care of them, but feels the children are not safe in the shacklands - something she believes will change if she gets a house.

Although she has access to electricity, she said most months she ran out of money and could not afford to buy power.

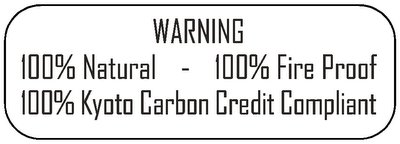

She is therefore forced to use paraffin and candles, which present a fire hazard to the children.

In addition, she is also concerned about hygiene.

Residents throw out dirty water in front of her shack and because of a lack of sanitation there is a risk of diarrhea and other diseases.

“This is not a place to raise children. I need a house so that my children can have a decent home, like other children,” she said. — West Cape News